Thoughts on Social Cohesion

Social cohesion and a response to the binary.

Our MSD submission.

I Initial premise(s)

- That the attention now being paid to social cohesion can fairly be seen as a direct consequence of the attacks on the mosques in Christchurch on 15 March 2019 and the recommendations made by the Royal Commission of Enquiry formed, with specific terms of reference, to enquire into a range of concerns around these attacks and their impact on, and implications for, society;

- That because of this, and though any work for social cohesion must examine a great many issues, as a starting point we must take learnings and initiatives from the mosque attacks as an important point of departure;

- These attacks were on a community defined by a specific religious faith – Islam – but constituted of a wide range of ethnicities and with members from 45 – 50 different countries of origin. The attacker targeted faith and not ethnicity, although he effectively conflated the two as being antithetical to his own notions of what could be considered to count as “white identity.”

- Any programmes setting out to work for greater social cohesion must have the ability to recognise faith as a force to be addressed, and yet be able to work across perceived boundaries of faith and non-faith;

- That being so, and given the genesis and focus of Mahia Te Aroha / The Christchurch Invitation as a community generated initiative that began in the Muslim community of Christchurch, the focus of this submission will be on the relation between any discussion of social cohesion and how this relates to the lessons that can be drawn from the killings of March 15, the response of the targeted community, the wider consequent public response, and the work that should be done, and might be done, for community and nation;

- This response of compassion we see as the antithesis of the binary, “for us or against us” response that came after the attacks in the USA of “9/11” – a binary response that has led to more than 20 years of war, to widespread destruction and loss of life, to a climate of mistrust and fear, and – in many cases – to attitudes and policies of exclusion. The response to the Christchurch attacks offers the possibility of a way forward that is nuanced and inclusive;

- At the same time we stress that the forces that work against social cohesion are many and that the local (Aotearoa / New Zealand) context, whilst having unique features and potentials, cannot be divorced from global forces and structures and assumptions;

- Global forces and dynamics (albeit with an appeal to certain vocal sections of New Zealand society) informed the man who brought his hate and slaughter to Christchurch in March 2019;

- (As an aside, this may mean that the time has now passed when a Prime Minister – however grounded and very approachable – can appear in a comedy skit [with Rhys Darby] premised on New Zealand’s being “missing from world maps.” Any sense of comfortable isolation has been breached and we cannot remain immune from precedents and examples from other societies);

- Given the frequency of examples from across the world of terrorist attacks on minority communities the sad lesson that caution demands is to recognise that an attack such as that which targeted the Muslim community could be experienced by any other minority community or, in fact, any grouping of people in society;

- That then demands:

a. a recognition of “fault lines” in society and of “identifiers” – ie, features or labels or characteristics that might be taken as “justifications” for an attack;

b. a recognition of where potential(s) and strengths might lie in overcoming those fault lines, and . . .

c. a need to examine areas in which Government or Government Agencies or existing structures might be constrained in their operations and in their ability to offer solutions;

12. Which brings us back to the question of faith and religion and their significance in a society that is secular in nature and in which it is

unlikely that Government can be well placed or best placed to take the lead in initiatives for social cohesion that might require

different faiths or traditions to work constructively with one another;

13. Mahia Te Aroha / The Christchurch Invitation speaks to that space and offers a platform for inclusive conversations.

II What is social “cohesion”?

We remind ourselves that we speak of Social “Cohesion.” The prefix has significance. All that which divides people, or has the capacity to divide, provides the opportunity for scapegoating and othering and must, therefore, hinder any work for social cohesion.

· It’s cohesion, cohere . . . coming and being and belonging together; sticking together; complementariness

· It’s not adhesion, adhere . . . sticking to something

To cohere is to stick or hold together as different, even unique, parts of the same mass or body, in a way that binds, and resists separation. The whole is stronger through that binding.

III Who determines who it is that belongs?

The contrary tendency is that state which breaks apart easily; a condition in a society that might deem some parts as not belonging; as apart from; as “othered.” Worse, perceived of as being parasitic on those who see themselves as the “host,” the centre, the true people of that place; and as not contributing, even invading.

That condition might come from a small group in a society (supremacists, racists, people carrying hurt); it might even come from “ordinary” people, as a consequence of something implied by the unexamined or insufficiently examined, connotations of a dominant or standard history. This begs questions about the history and histories we are taught – explicitly or implicitly – as the national narrative; and the stories and histories we are not taught.

In Christchurch in March 2019 we witnessed the (inevitable?) bloody conclusion of one force in society, fixed on a particular interpretation of history and on a certain world view that would determine which people would not be allowed to cohere together.

IV Overview of Issues that work against social cohesion

There are so many issues that have the power to set people against people; communities against communities; and that can work to foment a sense of seeing others as a perceived threat. Left un-tackled, many of the elements above – individually or combined – will remain as “elephants in the room.”

These might be deemed to be outside the remit of this particular enquiry but in a brief “second section” of this submission (at Para 8) we make reference to some of them

Restricting the scope of this submission

This submission is centred on one particular initiative that we consider has something to offer as a tool in the task ahead: Mahia Te Aroha /The Christchurch Invitation.

V What is Mahia Te Aroha? What might it offer?

I write as a co-founder of, and on behalf of, “Mahia Te Aroha / The Christchurch Invitation.” We understand Mahia Te Aroha as the call to “Action the Compassion!” This was launched in Christchurch on 23 July 2021 (see https://www.mahiatearoha.nz).

(I also write as a member [for almost 22 years] of the Deans Avenue mosque community in Christchurch).

Mahia Te Aroha is an initiative that begun by a small group of people in the Muslim community (Ben Gresham, Rob Dewhirst, and myself, Anthony Green) as a result of:

i the immediate identifying of the attacks as being an act of terror;

ii. the seemingly unexpected response of compassion and openness that came from the community that had been attacked; [nb, It deserves comment that if that response were unanticipated and if it were contrary to expectations then the ways in which stories are constructed about different communities should be open to question. Who tells the stories?]

iii. our recognition of the embracing response of compassion from the wider community that followed March 2019; and . . .

iv. the sense that there was in this something unique, and the possibility, if captured and harnessed and supported, of offering a way forward that might avoid the pitfalls that have dogged Western responses to terror to date and that have led to division instead of healing and growth; to destruction and displacement; and to loss and the denial of hope;

v. We saw difference as a source of strength, and argued that “a stronger ‘you’ is a stronger ‘us’”

That initial team has since grown and has been greatly helped in its development by Seed the Change | He Kākano Hāpai.

VI What can we offer that might not be possible from other groups?

The historical facts will be that:

i. this was an attack on people at prayer and following one religion;

ii. Watching and reading of processions of other such attacks on minority communities around the globe teaches caution and offers lessons: that (we hope it never happens) the violence and evil that came to the Christchurch Muslim community could happen to any other minority community in this country;

iii. Those who act in the same way as this man who came to murder will always find other groups to target. Theirs is a pathway that seeks others to blame and to punish for their own frustrations and angers; their “solutions” do not lie within;

iv. The response from the Muslim community was never to succumb to talk of vengeance but to act with compassion; and so:

v. A plan of action going forward would need to work like an invitation: generate opportunities and platforms for quite different views to work together; i.e., that difference would need to be harnessed and compassion could be the central focus;

vi. A special strength can be recognised if those who make the invitation to work together for an inclusive future, themselves come from the Muslim community but speak from a perspective that recognises that this demands that they work to ensure that bridges of respect and listening are built so that others are spared what happened such attacks.

Our starting point was to identify a message from the Muslim community of simple actions that might serve as some kind of common ground and that could speak to people across faith traditions and cultural traditions and that would also work for people who did not subscribe to any faith.

Our reason? It seemed clear to us that a story had been built up that set all Muslims as somehow driven by a tendency toward violence. We are well aware of events in the wider world and we reject any call to violence.

Indigenous values for belonging

We took our stand around the values of compassion, respect for others, and the desire that we could work for “authentic belonging.” In this we saw indigenous concepts such as Kaitiakitanga and Manaakitanga and Aroha as powerful ways of believing and acting that could create a vocabulary for belonging that may not be present in western, materialistic, secular world views.

VII Our four “simple actions” – and our launch

We based our starting point around a teaching from Islam that, when asked what was the work for the multi-faith, multi-tribe community of Madinah, the Prophet Muhammad advised, “Spread Peace, Feed others, Honour ties of kinship, and Pray at night when others are asleep.”

For secular New Zealand we interpreted that to be: “Spread peace, Share kai, Reconnect, and Reflect.”

Because we are seeking to generate inclusive conversations (the subject and the emphases of which cannot be pre-determined), and because we wish to work for authentic belonging, we factored different voices into our launch at the James Hay Theatre, Christchurch Town Hall.

The “keynote speech” can be viewed at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42QdbKE3NxY

This was followed by four young speakers from different backgrounds and ethnicities:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OjhA_gsPwCs

The speakers were Sara, Maha, Tyla, Will, Sam and Okirano. Among our speakers some had lost loved ones in the shootings, others non-muslim, Māori-muslim. We could go on. They all came together with unity and sharing their own stories of belonging (or not). The audience found the evening very impressive – honest, and brave.

Other initiatives

We are following this up with contact with schools to discuss techniques for harnessing differences. This is just the beginning of our work. We have a number of other initiatives and links that we are exploring. These include the working relationship that we have developed with two stage practitioners at the Juilliard School in New York, in the USA.

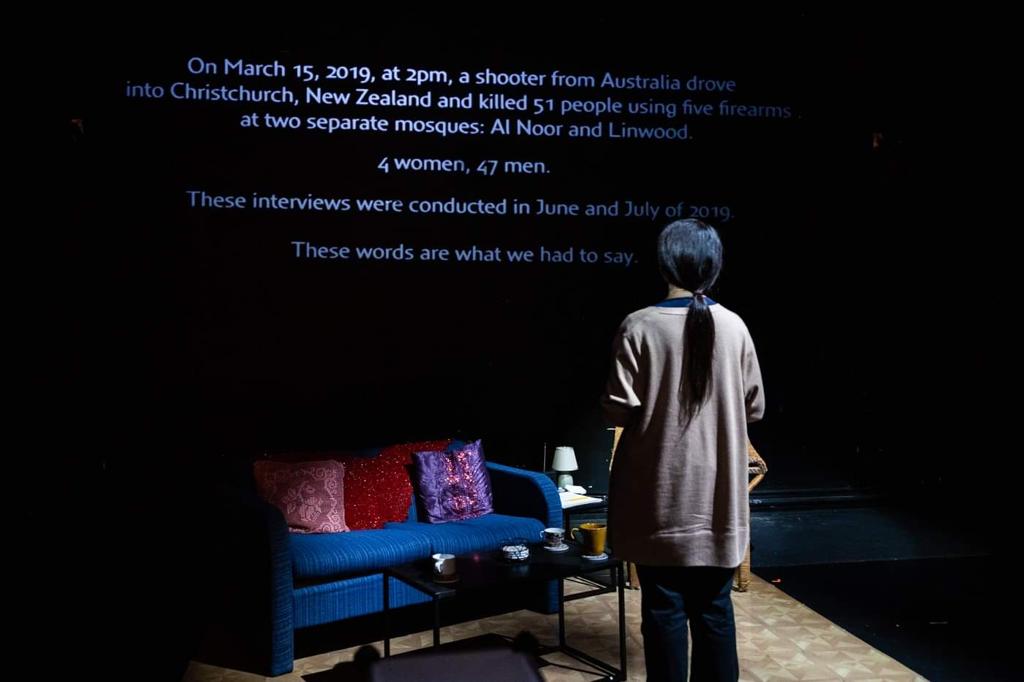

On Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday – 27 – 29 October 2021, the play “Memorial” was presented at the La Guardia Performing Arts Center in Queens, New York. This is a verbatim play that shapes the actual words spoken by five people from the Christchurch Muslim community who suffered loss. The writers and developers of this have been Arianna Stucki and Adam Elsayigh and the process of the development of the play has been in communication with the original speakers here in Christchurch. This is completely opposite to the manner in which Hollywood film makers have effectively appropriated the stories of people here.

Mahia Te Aroha recognises the need to give respectful voice to people’s own stories if we are to understand and respect one another. Story-telling, listening, being able to have your story heard: these are part of the work of Mahia Te Aroha.

Challenges [and possibilities]

There is a great deal that can be done but, even though we believe we can offer a unique perspective on, and pathway to, social cohesion, we are constrained by lack of capacity.

VIII Some other issues to consider

There a great many other issues that will conspire together to disrupt social cohesion but that fall outside what we can consider. The work for social cohesion is not achieved through an approach that limits enquiry.

In Para 2 above we said that,

“All that which divides people or has the capacity to divide, provides the opportunity for scapegoating and othering.”

Some possible causes of division in society that could lead to othering might include:

8.1 Education

In his so-called “Manifesto,” the man who came here to carry out slaughter referred to Muslims as “invaders.” He was white, of European descent, and Australian. White settlements in Australia began with the “First Fleet” in 1788. Indigenous Australians have been on that land for 50,000 years or more. That is well-known but not admitted amongst certain people. There is a great deal to be reflected on and much work to be done.

8.2 The feeling and the price of not belonging – examples from overseas

When young people feel that there are no opportunities for them, or that they are somehow not able to belong in the mainstream of society, while respecting their own cultural identity, we can see the sources of disaffection and then alienation. This is particularly relevant for those who are from non-European descent. It can be seen in countries like France, in the banlieues that exist around major cities like Paris, Lyons, and Marseille.

There are many other examples that be drawn from across the world.

The shape of New Zealand’s population is changing considerably. Taking as an example the Muslim community in Christchurch we have young people who are articulate, personable, intelligent and very well educated but who don’t find it easy to get work. That can be exacerbated in the case of Muslim women wearing a hijab (head scarf).

New Zealand is not France – the population numbers and population densities are very different but proactive measures based on the recognition of negative, even violent, outcomes overseas are much to preferred to inaction based on assumptions that “these things can’t happen here.”

8.3 Economic disparities: this is a very significant issue globally and increasingly so here in New Zealand.

A globally-dominant “neo-liberal” economic model has seen and continues to see huge differences in earnings and wealth. This model has generated the “gig economy,” short-term contract employment, and the near-impossibility for many families to survive on a single income. It is a situation that does not work for the promotion of a sense of community. Average incomes may be well below median incomes and new migrants will be seen as a threat by those who are low on the earnings ladder.

Economic disparities cause some to feel that they have no part in the claimed successes of an economy. Books like “The Spirit Level” or Joseph Stiglitz’s “The Great Divide” or the work of Jeffrey Sachs document and speak powerfully to the deleterious effects on this for economies and societies and their harmony and cohesion.

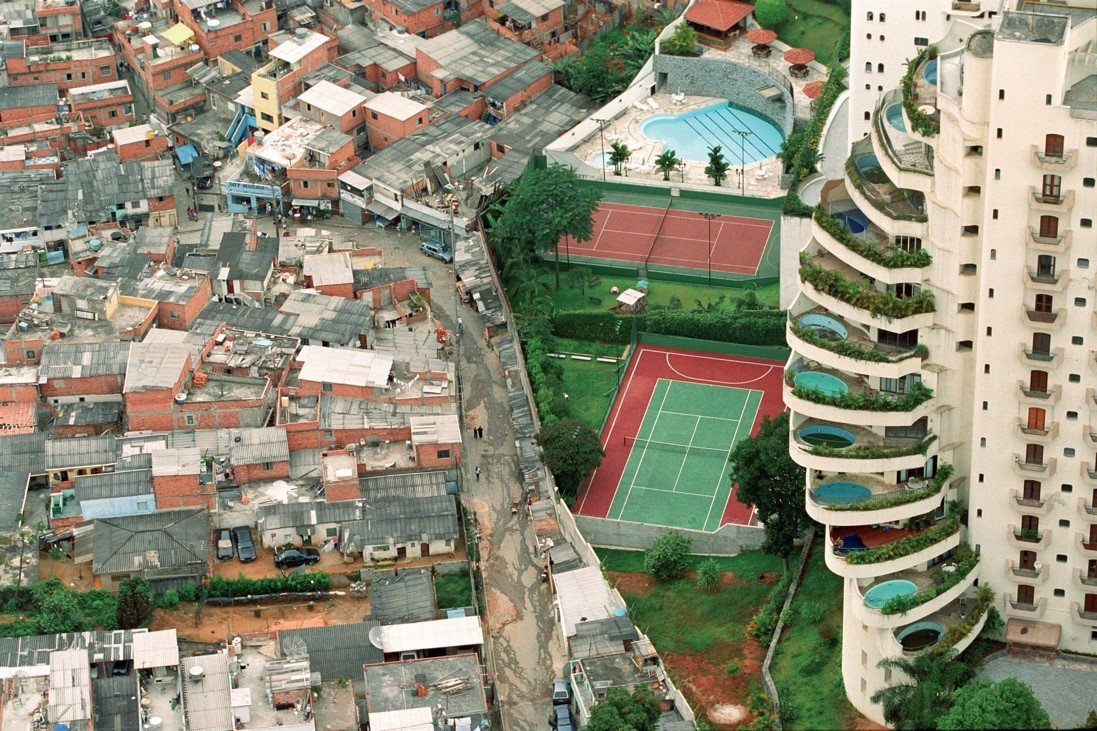

When economic divides grow to extremes, the task of building social cohesion becomes that much harder. This photograph by the Brazilian photographer, Tuca Vieira, is of Paraisópolis (“Paradise City” is the name of the favela in Sâo Paolo, Brazil).

These issues are beyond the scope of our submission but it should be recognised that when economic disparities become marked they create fertile ground for the scapegoating and blaming of communities and the work of “othering” of minority communities.